A sculptor who makes furniture? A furniture maker who makes sculpture? It doesn’t matter, although one suspects that on the long stretch, Joseph Walsh will have a secure place in the history of art, not just in Ireland, but wherever great art is appreciated.

Above: Sculptor and designer Joseph Walsh.

It’s easy to see why, or perhaps to feel why, because to stand under one of his monumental pieces and to walk around it is to both see and feel art, without having to touch it. Like a classic work by Mark Rothko, for example, it speaks not just to our visual senses, but to our souls. And it does it simply, without complication. If brevity is the soul of wit, then simplicity is the soul of art.

And his material of choice is wood.

“I started with timber very young”, he says, “and that gives you an intuitive understanding of it… you’re always learning and pushing your ambitions, so it’s a constant to and fro, the ambition of doing something new. There’s still so much to learn that I’ll probably continue on this road for some time to come.”

Above: Magnus V, a freeform sculpture in ash, reaching five metres in height, was unveiled at the Making In seminar in 2018. It embodies the Taoism philosophy of emptiness, believing that the mood should be captured as much in the imagination as the physically present.

Many good sculptors have taken a small piece and tried to enlarge it, unsuccessfully, because space makes its own demands on form. Only a piece that has been designed to perfection, if such a concept exists, will work at any size, for reasons that have as much to do with visual aesthetics as technique and engineering. Large-scale sculptural work usually shows what keeps it up, whether it be extra-thick bases or additional supports, but looking up at a work by Joseph Walsh, seemingly floating in the air, one marvels at the skill and engineering required to keep it standing. Although to say it occupies space very well is something of a cliche, it does just that. In fact, it appears to envelope all the space around it, as well as the viewer looking up at it. Its impact is such that one could say (with due respect to the correct use of words) that his work is stunning.

Above: Joseph Walsh created the Enignum VI Canopy Bed – Chatsworth for the exhibition Modern Makers in Chatsworth House, Derbyshire in England.Taking Chatsworth, and the Devonshire Collection, as a source of inspiration, Modern Makers is a unique selling exhibition of contemporary craft, hosted by Sotheby’s.

One might also be tempted to marvel at the fact that it all comes from a barn-like studio on a farm in West Cork, but that would be a mistake. He answers our question about location in a much more prosaic way, assuring us that there are pros and cons to operating in such a relatively isolated environment, but the truth lies parallel: he probably would not be doing what he does if he didn’t live and work there, because his work relates strongly to his natural surroundings. “I need a certain scale and space to work, and I have it out here in the countryside”, he says.

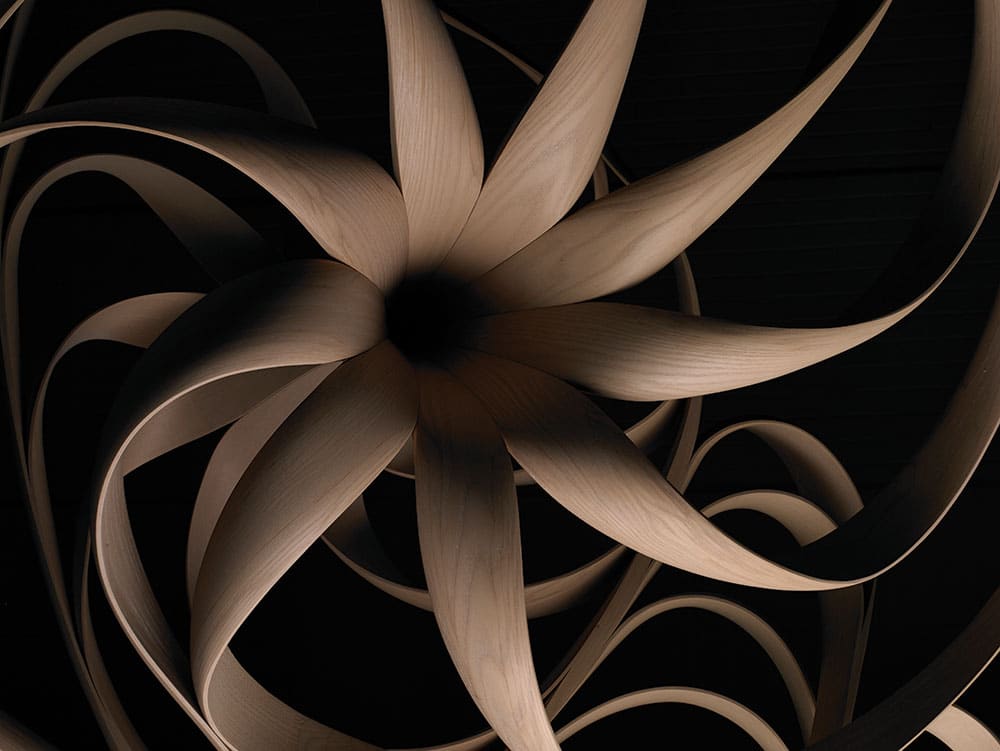

Above: The Lilium Series. “The Lilium series is both a study and an expression of the relationship between the beauty we create and the beauty we allow to happen; the beauty we participate in creating and the beauty we quietly observe.”

One can almost see, in his pieces, the winter wind howling across the West Cork landscape, bending the trees and setting our imaginations alight. One can feel the material he uses, knowing it comes from the countryside surrounding his studio, or from a similar type of landscape elsewhere. And knowing where he is from, one can imagine the lifelong relationship he has had with that material.

“There’s a strong sense of community among designers here”, he told us, “and that, I suppose, is the result of our relative isolation. We work together with a joint sense of purpose, far from the major outlets like London and Paris, but it’s a real luxury to be able to work in the place you grew up in. It’s something we might take for granted, but it’s rare”.

Above: Joseph in his studio in the West Cork countryside.

It may also come as a surprise to know that he has no formal training. His Wikipedia entry describes him as a self-taught furniture maker and designer, founding his studio and workshop in 1999 and exhibiting worldwide. But the story goes back further, to a time when he ran around the family farm looking for things to fix and things to make, as many a young fellow had done all over rural Ireland for many a long day. The difference is that he kept doing it, and that he was born into a time when the image of the designer as an exotic foreigner dressed like a rock star had long passed, thanks, in some large part, to the establishment of the Kilkenny Design Workshops long before Joseph was born.

Above: The Enignum Table Series – “The title derives from the Latin words Enigma (mystery) and Lignum (wood), for me they sum up the series: the mystery of the composition lies in the material.”

“It’s true that I didn’t go to art college but studied nevertheless,” he says. “I learned a lot from books about techniques of the past, I pursued knowledge, and that enabled me to take my own road and make things that hadn’t been made before. Reading, practice, travelling to see other people’s work, so I guess self-taught might not be strictly correct.”

Speaking to Joseph, we discovered a soft-spoken man on whom success and a growing worldwide reputation sits lightly but comfortably. Perhaps because he was never held up like a trophy at an early age as the next big thing of the international design scene, but grew into becoming what he now is under his own steam, he has kept his head firmly on his shoulders. Despite being a design and architecture magazine, our interest in him is primarily as an artist (readers more interested in his furniture can check him out on YouTube), although we could easily have done a full feature on him as a product designer. Suffice it to say that you have guessed correctly: his furniture is as organically beautiful and as perfectly made as his sculpture. Indeed, with regard to some of the pieces, like his Enignum Canopy Bed, form happily outweighs function unless, for you, a bed is just a bed, rather than a fairytale confection of ash and silk organza.

Above: Perfect symmetry in the Enignum Chair Series. As a furniture maker, Joseph is acutely conscious of the importance of comfort and utility.

Although he started making furniture at the age of 12, had his first employee at the age of 18 and was participating in major trade fairs in Britain and Ireland by his mid-20s, his big break came in 2008, when he was still short of 30, with a solo exhibition titled Realisations, at the American Irish Historical Society on Fifth Avenue. Important commissions followed, and his creativity was sharpened by his return from New York City to West Cork. Exhibitions all over Europe and the Middle East, and at the age of 33, his name meant a lot more that what it says on his passport.

Seeing a Shinto quality in the simplicity and finish of his work, we asked, of course, about Japan.

Above: The Enignum Shelf, a beautiful piece of sculpture and a useful piece of furniture, reflects Joseph’s concept of effortless design harmony. In permanent collections in the Museum of Arts and Design, New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

“That’s a common question,” he answered, “and there’s no easy answer, because It’s my work and I’m based in Ireland. I have great respect and admiration for Japanese design and what they do with wood. They’re a relatively small island and we are too, so nature is always present for us. We don’t have a great manufacturing legacy but lean more towards handmade crafts. We’ve got an intimate proximity to materials and processes, and consequently use materials in a more poetic way, I suppose.”

One of his undoubted masterpieces is his Magnus Series, one of which (Magnus V) was shown in last year’s now annual Making In seminar, established by Joseph three years ago as a meeting place for Irish and international artists, designers, craftspeople and architects. But Magnus Modus, commissioned for the National Gallery of Ireland by the Office of Public Works, is the one most people will remember. In creating it, he worked closely with the Hanegan Peng architecture firm, who designed the space for it. There is hardly any need to comment on it, because this is one of these rare works of art that is exactly what it is. What you see is what you get. And if there is somebody out there who doesn’t get it, they’ll have a listing in the Guinness Book of Records.

Above: Magnus Modus, a seven-metre-high, free-form sculpture made of multiple layers of laminated olive ash wood that is on permanent collection in the courtyard of the National Gallery of Ireland. Resting upon a small Kilkenny marble base, the Magnus Modus delineates space in its slender aspect, stationed on a tiny footprint, reaching upwards and then outwards. As the sculpture ascends, it becomes lighter and reacts to subtle changes in the atmosphere.

So is it too facile? Does it have enough depth of meaning? Is it no more than a nicely twisted piece of ash made on a grand scale?

It is all of these things, and therein lies its genius. Absolute simplicity of form. Serene, elegant and exciting, all at the same time: it speaks as sweet and clear as the sound of the uilleann pipes in the hands of a master, and reminds us of the curved beauty of the La Tène motif of the ancient Celts. This is a work of art that reflects, not just the soul of art, but the soul of Ireland.

This article first

appeared in the

6th issue of

UD Magazine.

Click on the image to read online.